Can a nylon shuttle match one made of feathers? IIT researchers may have answer

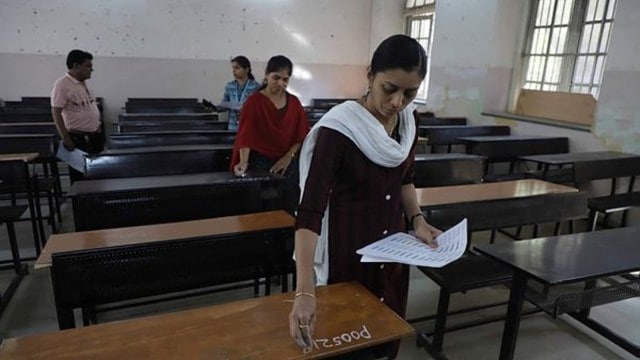

Every time Sanjay Mittal, 55, held a badminton shuttlecock made of feathers, all he thought of was the cruelty inflicted upon birds.

This got the IIT Kanpur aerospace engineering professor thinking. Could a nylon alternative replicate the flight pattern of a duck or goose feather shuttle that is used at the sport’s highest levels?

Last week, Physics of Fluids, a journal by the American Institute of Physics, published a research paper by Mittal and two other Indian scientists, Darshankumar Zala and Harish Dechiraju, that explored the aerodynamic performance of nylon shuttles at different flight speeds. Their article — ‘Computational analysis of the fluid–structure interactions of a synthetic badminton shuttlecock’ — studied how air flow and speed can deform the flared skirt of the shuttle.

This opens up the possibility for improved designs that can make the nylon shuttle stiffer, helping it accurately mimic a feather shuttle’s aerodynamic performance. “This could be a game-changer,” Mittal says.

Mittal, who has a keen interest in aerodynamic studies in sport, started playing badminton at clubs on the IIT Kanpur campus. Co-researcher Zala is a BTech student from Ahmedabad while Dechiraju is Mittal’s former student at IIT and currently a product application engineer with a semiconductor company in Chennai.

Mittal explains the key differences between nylon or synthetic shuttles and the ones made of goose or duck feathers. “Traditionally, a feather shuttle is brittle and becomes useless after a few shots. But it holds its shape longer than nylon. And there is the issue of cruelty to animals as well. There is a move to get in nylon shuttles from a sustainability point of view. But the aerodynamics are hugely different as the nylon one deforms in shape faster and turns too wobbly to continue playing. So our study has taken on the challenge to find out how to redistribute the nylon in a shuttle design so that it stays stiff at the right place and behaves exactly like the duck one,” he says.

A Badminton's shuttlecock must be extremely aerodynamically stable. This is how the shuttlecocks are calibrated

[???? https://t.co/hoaPBcimwf%5Dpic.twitter.com/KI8o5gn0dB

— Massimo (@Rainmaker1973) March 19, 2023

A shuttle typically weighs 5 grams — the cork makes up 1.5 grams and the skirt 3.5 grams. The pressure on a nylon shuttle at a speed above 40 metres per second (mps), or 89 miles per hour (mph), forces it to lose shape, altering its flight behavior as the vortex structure weakens. For context, shuttle speeds easily reach 300 mph.

“In a nylon shuttle, as it deforms, the air resistance is much less, and it starts becoming unstable. The speed increases so much that opponents have very little reaction time. Elite players don’t like such inconsistency. Duck shuttles stay stiff no matter what speed they are subjected to, because the coefficient of drag doesn’t vary,” Mittal says.

Studying the relative trajectory and drag on the two types of shuttles, by examining aerodynamic forces on the shuttlecock as well as its deformations at each flight speed, Mittal and his fellow researchers noticed patterns in nylon that are different from natural feathers. The outermost skirt of nylon shuttles tends to be flimsy and deforms inwards, upto 9 mm, asymmetrically. With reduced air resistance, the speed gets wild and uncontrollable.

Synthetic shuttles have high drag due to a pressure difference. Seventy-five per cent of the drag comes from the outer skirt. The centre of pressure in nylon shuttles is distributed more towards the cork, compared to a duck shuttle, where it’s towards the feathers.

The study also showed a process of buckling, where the shuttle sways vertically after 40 mps and the skirting starts getting rumpled. “Nylon shuttles buckle at 40 mps, then become an unstable square shape. Then they start vibrating radially and finally travel in a wave form. That’s wobbly and not very good to play,” Mittal says.

He compares this to batters tackling an uneven cricket pitch. “Players are used to a certain kind of shuttle where they can show their skills and want uniformity, not a struggle for survival. Duck is the gold standard right now. So, our studies are trying to find how to redistribute 3.5 grams of nylon into a shuttle skirt so that it behaves like a duck shuttle.”

Mittal says leading manufacturer Yonex brings out two nylon shuttles yearly, with thicker walls and more holes in the skirt. Though not his area of expertise, he reckons other composite materials beyond nylon, which is light and elastic, but not expensive and unamendable like carbon fibres, can be tested. “The goal is to redistribute nylon structure to mimic duck shuttle trajectories. The next step is to get designers to work on it,” he says.

While he says his research work can help designers tweak the structure, Mittal believes Indian coaches are astute about shuttle flights even if they may not possess scientific details. A fan of Chinese legend Lin Dan, he feels there’s a larger goal. “India has a big community of badminton players. But we import all gear — racquets, shuttles. Imagine if we can deploy science to develop our own designs, and then export equipment.”

Posts

Posts Sign up as a Teacher

Sign up as a Teacher