Indian schools treat math skills picked up at home and in classrooms as different: Nobel Laureate Esther DufloSubscriber Only

In a study published in the journal Nature, a team from the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL), including Nobel Prize-winning economists Esther Duflo and Abhijit Banerjee, found that children working in markets can do complex transactions as part of their job, but struggle with textbook math taught in schools, while children in schools work well with academic math problems, but don’t do as well in practical calculations.

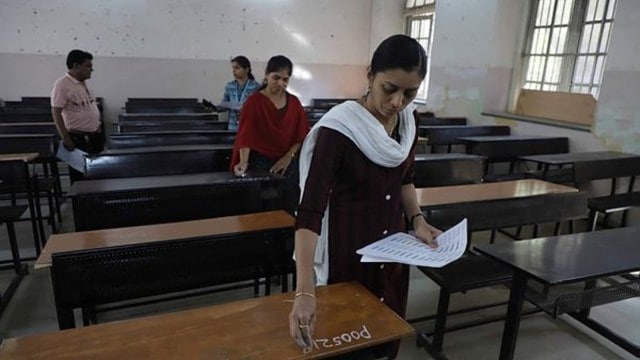

The study examined children in Delhi and Kolkata to understand how math skills transfer between real-world and classroom settings. In an interview with The Indian Express, Duflo discusses the findings and their implications for curriculum and teaching.

We’ve worked on education in India for over 20 years. The recent ASER report by Pratham shows progress in basic learning — a significant achievement. However, for years it has revealed low levels of basic math and learning achievement in primary schools and among adolescents. This contrasts sharply with what we observe in markets, where children easily handle transactions and calculate change.

The key is recognising existing knowledge. Children have math skills from various sources — markets, video games, farm work — but schools treat home knowledge and school knowledge as separate domains. We need to bridge this gap.

The current problem is that students learn algorithms without understanding. They’re taught specific solutions rather than problem-solving approaches.

We should encourage different approaches to problems. For older students, introducing estimation before calculation would help. Our successful early-grade interventions use collaborative games with self-checking mechanisms, though we haven’t fully explored this for middle school students (aged 13-15 years).

The practical application should be seen as complementary to theoretical learning, not a waste of time. The new education policy recognises this, especially in early grades where it encourages learning through games. Games help children own the knowledge when structured properly. For higher grades, this study suggests we need something similar to early-grade games — connecting theoretical knowledge with practical applications. This bridges the gap between existing practical knowledge and abstract concepts we want to teach.

There’s limited research on this — mainly one old anthropological study of Brazilian out-of-school children who showed strong calculation abilities.

In France, students perform poorly on PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment) tests, partly because they contain practical questions, while French math education is very abstract. So this is definitely something that seems to be true in France at least. Singapore’s curriculum tries to balance practical and theoretical problems.

But yes, this doesn’t seem to be unique. It’s perhaps more acute in countries like India or France that have curricula that are very abstract.

I think it comes from repeated exposure to the environment. They learn by observing others and then practising themselves. Whether self-taught or guided, they develop effective rules for arithmetic.

One common strategy they use is rounding. For example, instead of calculating 490 grams times Rs 50 the school way, they’ll multiply 500 by 50 and then subtract.

I think they capture exactly what they need to capture, which is whether the school system is managing to impart what it is trying to impart. What schools are trying to teach is for people to do division, subtraction, etc. And so, ASER or the national assessments are trying to capture that. I think that’s the right first step.

It’s measuring something specific, which is the understanding and ability to apply school math. What it does not measure is the fact that some kids might be able to do math when it’s not presented as school math, and that the kids who are able to do school math might not be able to apply this knowledge to other things. For that, there are other surveys; for example, from time to time, the regular ASER is replaced by one called Beyond Basics that also has practical questions.

What schools are trying to achieve, in the first place, is teaching basic arithmetic in a formal way. Our study is not saying that we shouldn’t try to teach that.

I think we need the ASER every year, and then maybe a more comprehensive survey that captures these more practical questions every three years or so. But there’s nothing in the study that says it’s not important to measure basic academic learning.

For the market kids, the fact that they have not mastered this basic academic learning means that even though they are very good at arithmetic, they will not succeed in school. They will not be able to learn more advanced things, even though they clearly have the mental skills to do it. We need to find a way to teach these skills to them.

In his G20 salvo, who is Marco Rubio targeting?Subscriber Only

Rationale behind RBI’s repo rate cutSubscriber Only

Gulzar's Aandhi is not just 'that film on Indira Gandhi'Subscriber Only

The rise of India’s premier boarding schoolsSubscriber Only

Anand Neelakantan: 'Many Ramayanas, Many Lessons'Subscriber Only

Delhi to Mexico: A man’s harrowing journey ends in deportationSubscriber Only

For Assam, why deporting 63 ‘foreigners’ is easier said thanSubscriber Only

How AK Gopalan's case became a benchmark for personal libertySubscriber Only

Why is the MPC likely to cut the repo rate?Subscriber Only

Delhi: At bottom of income ladder, AAP secureSubscriber Only

The story of India’s atomic slideSubscriber Only

Posts

Posts Sign up as a Teacher

Sign up as a Teacher