Why Rohit Sharma the Test batsman could redeem Rohit Sharma the leader

Rohit Sharma was sitting alone in the Wankhede dressing room after India were whitewashed 3-0 by the New Zealanders. His team-mates had left. The Kiwis were quietly celebrating in their dressing room, their occasional hoops of joy drifting across. The stadium staff talk about how Rohit just couldn’t get up and leave the arena. Not long ago, many of them had seen him at Wankhede, drenched in public adulation after the T20 World Cup triumph. Circle of life, perhaps.

Rohit isn’t in Perth and Jasprit Bumrah will lead in the first Test. Their pre-series coverage has been fixated, understandably, on Virat Kohli. Rohit, the captain and a star, has been reduced largely to a ghostly presence. But he has had far more pressing concerns of late: from parenthood to on-field headaches in recent times.

The loss to New Zealand jolted the system. Now, prior to the tour of Australia, it won’t be a surprise if there is a sinking feeling of anxiety, or at least tremendous uncertainty, in him. Added to it, the injuries to key players leaves India, and him, rather vulnerable.

There are two aspects to Rohit at this stage – the batsman and the leader, and both have overlapped in recent times, one overtly affecting the other.

Perhaps, it’s wise to delve into his most popular meme to see what kind of challenges he faces in a young inexperienced team. That ‘garden mey ghoomne waale log’ comment about the lack of intensity and cricketing intelligence in his team went viral as a positive bookmark to his earthy/desi style of leadership. But beneath the jocularity, in hindsight, especially as India won that series against England, its very existence reveals a lot about the youngsters in the team.

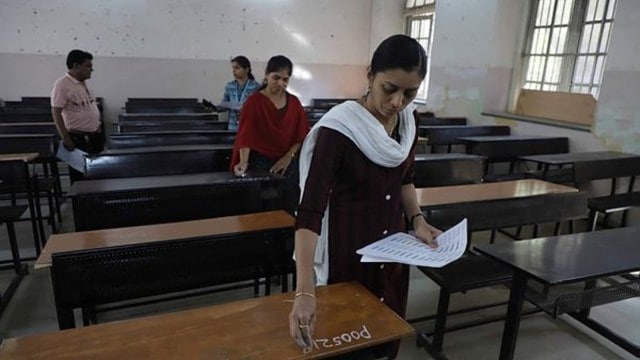

This is a team of young men largely emerging from IPL or age-group tournaments, without the hard lessons learnt in first-class cricket for any meaningful length of time. Barring Sarfaraz Khan. They haven’t toiled hard through seasons, raked their heads through campaigns, intimate with the art of building an innings or building spells by altering their tempo according to the demands of the sessions. Most of them have either spent bashing the ball in T20s or working hard at the nets on their individual skills of batting or bowling. This isn’t a complaint, just an observation about modern-day cricket. Captaincy came to Rohit at this stage in his life and Indian cricket in general.

He has had to teach them cricketing basics of how to attack as a pack of men on field. He had to teach them how to approach batting. He had to counsel them on how not to get carried away with a little bit of success. He had to speak to them about the dangers that await at the first stumble. Less than a year ago, Shubman Gill was almost dropped in the middle of the England series. Less than a year ago, Rishabh Pant was still in recovery. Mohammad Siraj couldn’t find his game in India. The state was also forced on Rohit’s management team as players who have some experience in domestic cricket like Shreyas Iyer, Rajat Patidar, Srikar Bharat, Mukesh Kumar couldn’t quite find their Test game. Those like Ishan Kishan had their own issues. Only the novices remained. A couple have developed leadership ambitions too.

Some of his predecessors could plan how to implement their ideology or philosophy on the team. Rohit has had to alter his to what he thinks this team of young men need.

Here is where Rohit the Test batsman has slipped. It’s one thing for him to don his all-out attacking role in white-ball cricket that admirably and inspirationally lifted an entire team out of a philosophical swamp of outdatedness in those formats. He decided to set the aggressive template to lead them to the promised dry land of run-feasts so that his bowlers can then all-out attack without concerns. That approach suited those formats; India had to be dragged out of self-imposed shackles. The white-ball team had lacked the sense of urgency that was direly needed and it was up to an ageing Rohit to show the youngsters the way.

The current Test team lacks a different sensibility: of grit, patience, adaptability, and intensity on field. Here the solution was Rohit’s own 2021 Test batting in England where he utterly transformed his urges to become one of the best compactly classical Test openers in world cricket.

It hadn’t come easy. Once in an interaction with this newspaper, weeks prior to the 2023 ODI World Cup, the talk veered to that transformation.

He looked around his hotel room for a bat, couldn’t find it as the kit was in the team bus and said: “I could have shown you my exact batting-grip change but what I can’t show you is the amount of pain in my wrists in trying to do it. It took a long time and I had to drastically change my old grip in order to tighten up, to be more compact. Not for any issues for lbw – that needed a footwork change – but to tackle the balls in the off-stump channel. How to keep leaving or keep playing the line so that any ball seaming or swinging away can go past the outside edge. I had to retune my muscle memory there – and it caused a lot of pain. But nothing is impossible once you feel the need to do it and apply yourself mentally to it.”

It will be interesting to see in Australia if he reverts to the 2021 mould or keeps attacking as he has done in recent times. The one thing he has consistently said recently is how the batsmen need to find way to get runs, keep scoring. “You have to look to get runs also and that’s how you try and put the bowlers under pressure,” he said after the series loss before adding: “We are sad. It is important to be sad. But, it does not mean that you have to change your entire system. Our system is that we are playing cricket in one way. We just need to change our style a little. That’s it.”

There is a genuine top-order vulnerability. This is the first Australian tour for the inform Yashasvi Jaiswal. Shubman Gill isn’t there for the first Test and barring Rishabh Pant, India’s main batsman, no one else is in a good space. Not Kohli, not KL Rahul. Dhruv Jurel probably is the batsman who has shown he has the game to play on those tracks but he hasn’t faced the international Test quality of Australia yet.

What approach is ideal, then, for Rohit? To try score some quick runs or see if he can show his team that the fire can be put out through patience, grit, and then once the Kookaburra ball eases up, attack. For the latter, he has to be in absolutely good space as it needs him to mix all dimensions of his batting.

The clincher is he needs to have confidence in the rest of the team that they are ready mentally, temperamentally and skill-wise. That they aren’t a disparate bunch who are just focussed on their own self, but have the character to extend themselves, look beyond themselves to forge as a unit. A team that doesn’t need to be told not to ‘meander around in the garden’, a team that doesn’t need to be told to wear helmet or abdomen guard while fielding at close-in positions, a team that doesn’t need to be told to switch positions automatically when a left-handed batsmen comes on strike, and attack as a group.

This is important, just like he showed them the ideal way in white-ball cricket with his own example, he has to guide them in red-ball batting. Whatever criticism one can land on him, it cannot be said he doesn’t care or he isn’t deeply conscientious. He is someone who is aware of the legacy of Indian cricket, does fret genuinely about the temperament and life-goals of youngsters.

However, this tour will come down to how Rohit the batsman bats – he doesn’t need the monastic abstinence that was required in challenging conditions of England with the constantly moving ball, but probably a more sensible start before he allows his attacking urges their rightful space. It would also come down to how he leads this team on the field, especially if India get off to a bad start in the first couple of Tests.

He returns to Australia, a place where he has seen selectorial disappointment in 2012, mixed feelings in 2014, happiness of a series win in 2018, and a witness to unadulterated joy in 2021, sitting on the stairs outside the dressing room at Brisbane when Pant’s off drive clinched a memorable series win.

How will this tour end for him? Alone at the SCG dressing room, wondering whether he should call time on his international career or revel in the joy of an inspirational turnaround in fortunes and looking forward to the Test tour of England in June with great confidence?

Posts

Posts Sign up as a Teacher

Sign up as a Teacher